“Every character, before they are heroes and villains, they are human beings.” — Tabu

Persuasion through storytelling is an art form. Some lawyers are naturally gifted at it, while others can struggle a bit. Like all art forms, storytelling has conventions, ways in which things are usually done.

Ask any storyteller and they’ll tell you that there are conventional characters and structures common to most every story: The story centers on a hero who lives in a world that is status quo for such a character. Whether the main character is a ragpicker, an executive, a punk rock star, or a teacher, they live in a world which is basically in balance. Then, something happens to throw their world out of balance, a cause of disharmony or conflict, a problem. The hero thus wants to solve the problem and restore their world to balance.

But something is standing in their way, an obstacle. Sometimes that obstacle is nature (think the vast ocean in Castaway) or society (think the subjugation of women in The Handmaid’s Tale), but very often it is someone else, a villain. Examples are easy to come by, the Wicked Witch of the West, Darth Vader, or Major Strasser, the personification of the Nazis, in Casablanca.

Admittedly, the terms “hero” and “villain” are not ideal. The “hero” character is not always so “heroic” and some “villains” lack the evil intent the label implies. Suffice to say that the terms “hero” and “villain” are meant to be understood in a broad way.

As we hear a story, we (most often unconsciously) come to understand who the hero is and who is the villain. Storytelling conventions do not just apply to stories we consume as entertainment. Our brains are hardwired to think of our worlds in terms of stories. Noted cognitive psychologists Roger Schank and Robert Abelson once wrote, “Storytelling and understanding are functionally the same thing.” Everything and everyone are potential characters in the stories of how our world works. This is one reason why storytelling can be so persuasive; it fits with how we make sense of the world.

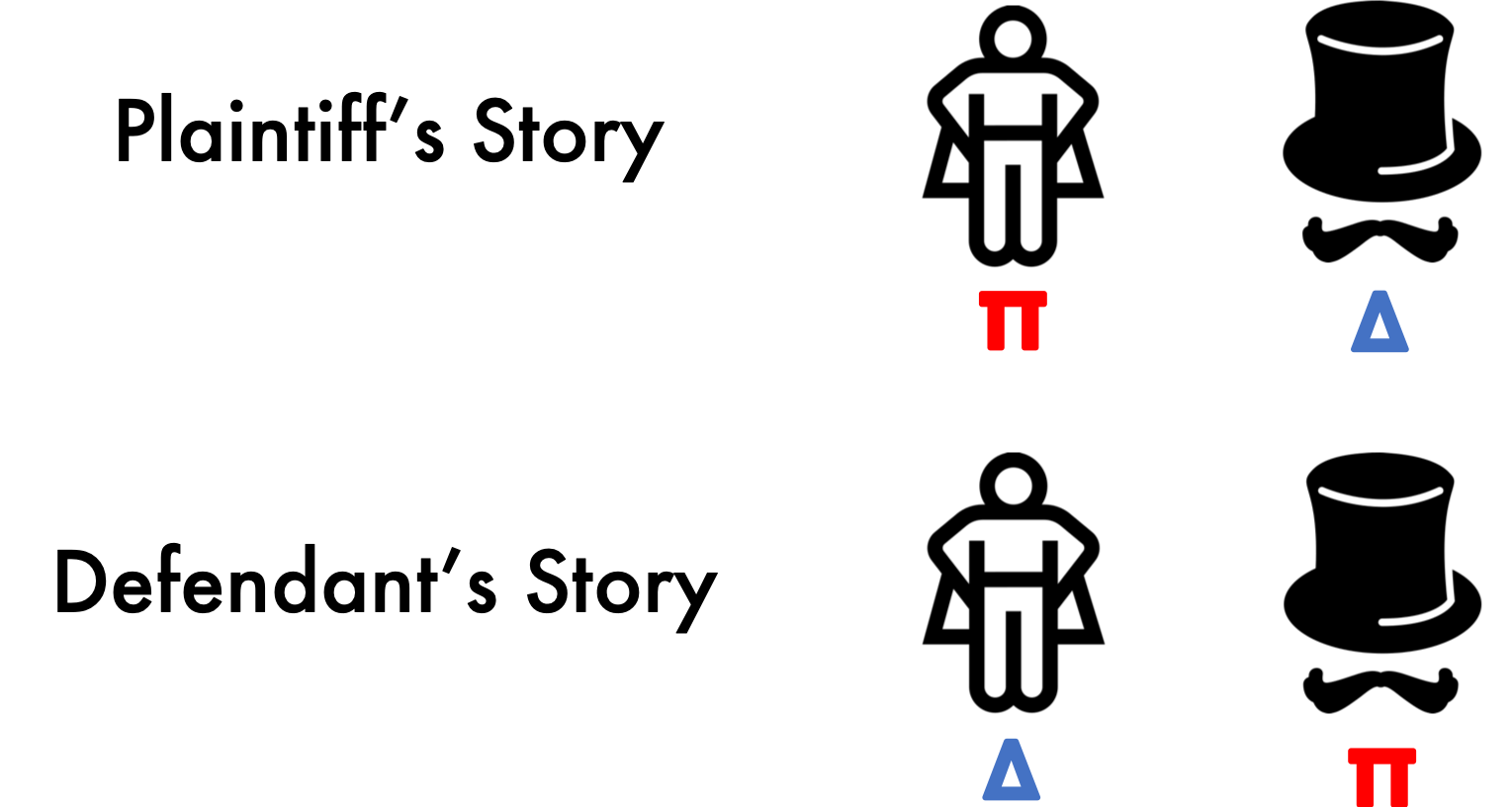

To the extent that litigators and trial attorneys create a story of their case, they tend to be fairly conventional in terms of who they cast as the hero and the villain. For Defense (∆) attorneys and Plaintiff (π) attorneys alike, their client is the hero, while the other side represents the villain.

On the Plaintiff side sits a hero whose previous status quo life was thrown out of balance by the action or inaction of the villain Defendant. On the Defense side, a hero believes they are being falsely accused by the villainous Plaintiff. These are the usual roles the two sides assign to themselves and to the other side. But do they lead to the best story about their client’s case?

Here’s a thought experiment. If you are a Defense attorney, imagine that you are defending your client against a Plaintiff. Assume the harm the Plaintiff is experiencing is legitimate. Now, imagine that, instead of defending your client against the Plaintiff, you assume the role of another, secondary Plaintiff with claims against a different “Defendant.” Confused? Perhaps some real-world examples will clarify.

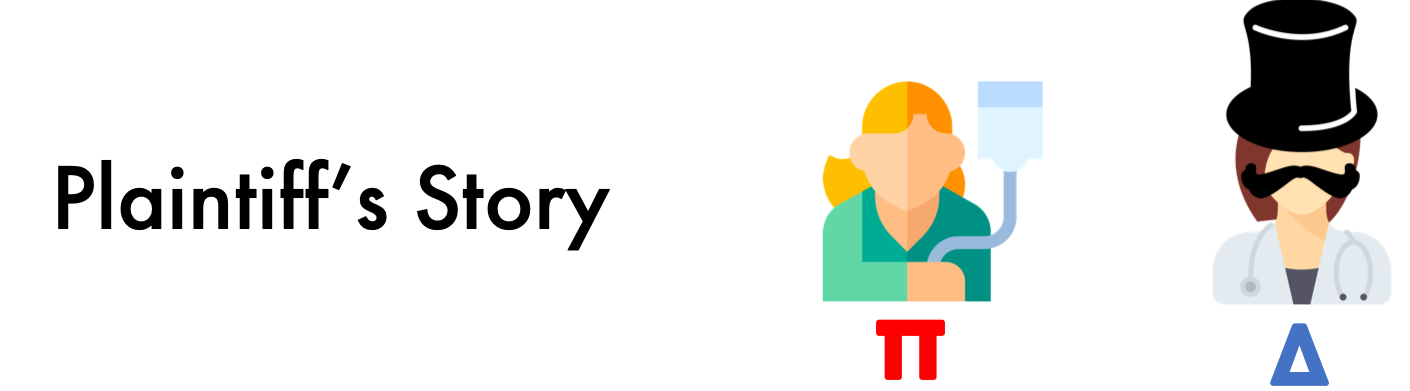

We were recently involved in a medical malpractice case in which a patient was suing a doctor that we helped represent. The Plaintiff claimed that when the doctor was excising a tumor (that the doctor thought was benign) and cut into it, the doctor unwittingly spilled cancer cells into the surrounding tissue. Had the doctor not cut into the encapsulated tumor, the cancer would not have spread. As it was, the Plaintiff’s cancer soon returned to the same general area and, despite chemotherapy and radiation treatments, spread to her lymph nodes. It was likely terminal.

For the Plaintiff, the roles were standard. The Plaintiff was the hero character who, prior to this surgery, was living her status quo life, but she had a problem. She had what her doctor thought was a benign tumor that she needed removed. She took steps to have her tumor removed, but she didn’t realize that her doctor was a villain whose negligence, if not sheer incompetence, created an even worse problem in the Plaintiff’s life. The Plaintiff tried to solve the problem through chemo and radiation, to no avail. The villainous Defendant exposed her tissue to cancer cells, which will likely lead to her death, and will not take responsibility for it.

The more traditional Defense in such a case would be to argue that you cannot “seed” tissues with cancer cells (the Plaintiff’s experts are lying), or the Plaintiff somehow unreasonably delayed getting her tumor removed and allowed the cancer to spread (the Plaintiff’s fault), or the cancer would have spread anyway (the Plaintiff’s fate). We recommended a shift in the role of the hero defendant and villain.

In the Defense’s new story, the doctor was still a hero. Her status quo world centered around alleviating her patients’ disease. The Plaintiff caused a problem for the doctor, but it wasn’t because the Plaintiff accused her of violating the standard of care. The Plaintiff had cancer, which is the most serious obstacle to the doctor’s goal of alleviating her patients’ disease. Mysterious, random, and virulent cancer. For the hero doctor, cancer was the villain. Rather than positioning the Defense in opposition to the Plaintiff, who through no fault of her own was dying from cancer, mind you, the Defense took on the role of a secondary Plaintiff with cancer as an alternative Defendant. The strategy defied juror expectations in part because the Defense was not the least bit defensive toward the Plaintiff’s accusations. We were focused on the cancer, which was easier for jurors to accept as a wicked villain than a competent and well-intentioned doctor. In the end, the jury returned a defense verdict.

The identity of the hero on the Defendant side can also be manipulated. In a recent labor and employment case, a long-time employee of a military contractor sued claiming a manager had retaliated against him. For those who do not work in Labor and Employment law, a claim of retaliation usually involves three elements: 1) the employee must engage in a protected activity, e.g., reporting what the employee reasonably believed was the employer’s illegal activity to a government or law enforcement agency, i.e., whistleblowing ; 2) suffering some adverse employment action, e.g., being terminated, demoted, etc.; and 3) a causal nexus between the protected activity and the adverse employment action.

The manager had come in, eventually bringing in a new assistant manager, to oversee a new government contract. The employee complained to upper management that the new manager was responsible for waste, fraud, and abuse in implementing the new contract (the protected activity). He was eventually terminated (the adverse action). The causal nexus was essentially implicit.

From the Plaintiff’s perspective, the Plaintiff was a hero whose long-time experience at the military contracting company made him an expert in how things were always done. The new manager and his new assistant manager were implementing new policies and procedures. This was upsetting the status quo, which was problem for the Plaintiff. The Plaintiff was highly suspicious of the new ways and took it upon himself to ferret out the alleged waste, fraud, and abuse and report it to the government. He had hoped this would restore the status quo. From the Plaintiff side, the manager was a corrupt, villain Defendant.

The more traditional Defense would be to attack the character of the Plaintiff. “He was the WORST employee in the world,” they argue. Jurors, who by and large relate more to the Plaintiff than the manager, ask with suspicion, “Then why did you hire him and why did he continued to work for you for decades?”

Mock trial research confirmed that jurors rejected the Defense’s attempt to paint the Plaintiff as a bad person. It also revealed that jurors did not like the manager. However, jurors were very favorably inclined toward the assistant manager, who they saw as hardworking and charming.

We recommended that the Defense abandon any attempt to attack the Plaintiff personally and shift its focus to make the new assistant manager the hero of a secondary Plaintiff’s story. As an assistant manager, her status quo was implementing performance improvements through new policies and procedures on the factory floor. However, she had a problem. She was being constantly thwarted by the Plaintiff, the very mildly villainous Defendant (just a mustache, no hat) who mindlessly opposed any type of change, thereby stifling any chance of improvement. The Plaintiff’s counsel’s focus was on the manager, allowing the assistant manager to play the hero role in the Defense’s new story virtually unopposed. The case ended with a very favorable settlement for our client.

Many of the Plaintiff strategies popularized through books like Don Keenan and David Ball’s Reptile actually implement this sort of role switching or modification. From the Plaintiff’s perspective, the Defendant is not only the villain, but a stand-in for larger systemic injustices. And while normally the hero on the Plaintiff side is the actual Plaintiff, these strategies subtly transfer the role of the hero to the jurors themselves. These “hero-jurors” are presented with a challenge to their and their loved ones’ safety and called to action to neutralize the danger and disorder the villain Defendant represents by awarding large damages. This is one reason why traditional defenses to these strategies, which focus on painting the actual Plaintiff as the villain, are so often ineffective. These defenses are not responsive to the Plaintiff’s story’s “true villain,” the larger systemic injustices and the danger they cause.

Persuasion through storytelling is an art form, so being mindful of the tendency to tell a conventional story is essential to effective storytelling and advocacy. Modifying or switching the identity of the hero or villain can be an effective means of persuading any trier of fact. What is more, it allows Plaintiff and Defense counsel to tell a novel and memorable story that helps delineate their story from the other side’s.

John G. McCabe, Ph.D., is a cognitive psychologist and senior trial consultant. For over fourteen years, John has designed and performed a wide variety of studies (focus groups, mock trials, etc.) related to jury decision-making. Results from these studies have informed trial strategy in a wide variety of civil and criminal cases. He also assists in preparing witnesses, composing voir dire questions, jury selection, writing draft opening statements and closing arguments, developing trial graphics, as well as performing in-court observation and post-trial interviews with actual jurors. He earned his Ph.D. from Claremont, where his research focused exclusively on juror and jury decision-making and bias. In a prior life, John enjoyed a 15-year career in the motion picture industry, where he honed his understanding of storytelling.

John’s writings have been published in prestigious psychology and law journals and he has spoken at numerous national psychology and law conferences, law schools, colleges, bar association meetings, and Inns of Court. He has also published articles in For The Defense, Verdict Magazine, Trial Practice Journal, Women Lawyers Journal, Of Counsel, The Daily Journal, and TortSource, and his commentary has been published in the Los Angeles Times, Law360, and Bloomberg News. John has also appeared on television including CNN, HLN, and TruTV, where he discussed jury and juror behavior.

All icons used in this article were made by Freepik and Eucalip at www.flaticon.com.

Recent Comments