“Neither revolution nor reformation can ultimately change a society, rather you must tell a more powerful tale, one so persuasive that it sweeps away the old myths and becomes the preferred story….” — Ivan Illich, Storytelling or Myth-making?

So, what does make a good case story? The question reminds me of my days in graduate school. After 15 years of working in Hollywood, I decided to make a radical change in careers and pursue trial consulting. My reason for wanting the change is best summed up by the one liner: What’s the definition of “a friend” in Hollywood? Someone who will stab you in the front! I chose trial consulting because I’ve always had an abiding interest in psychology. Also, I come from a family full of lawyers and although I never wanted to be one, I’ve always respected and admired the legal field. Having chosen trial consulting, I went to graduate school because I needed to know more about how jurors and juries make decisions. Things were going well. I liked my classes and my advisor.

Then one day my advisor introduced me to the research of Nancy Pennington and Reid Hastie. Over years of psycho-legal research experiments,  Pennington and Hastie developed the Story Model of juror decision-making. The Story Model is not a predictive model of outcomes in decision-making, but rather an explanatory model used post hoc to describe the process jurors and judges go through in rendering verdicts. The model was developed primarily using criminal cases.

Pennington and Hastie developed the Story Model of juror decision-making. The Story Model is not a predictive model of outcomes in decision-making, but rather an explanatory model used post hoc to describe the process jurors and judges go through in rendering verdicts. The model was developed primarily using criminal cases.

The Story Model assumes that in nearly all cases jurors will organize the information gleaned from testimony and exhibits into potential narratives rooted in their knowledge of both the world and story structures. Nothing I’ve seen in my many years of trial consulting leads me to question this assumption. These stories are essentially compared to each other based on several criteria until one wins out as the story of “what really happened.” That accepted story, along with information from the judge’s instructions and the juror’s prior knowledge of different criminal charges, is then matched with the appropriate verdict option.

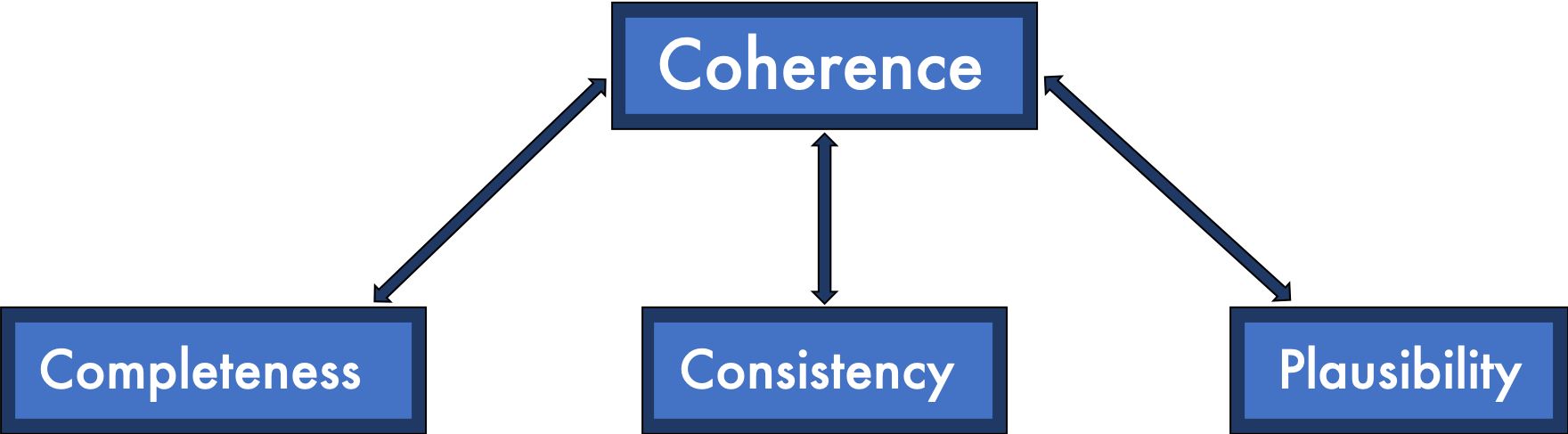

Pennington’s and Hastie’s chief criterion which triers of fact use to judge potential stories is coherence. Coherence is made up of three sub-criteria: completeness, consistency, and plausibility. To judge a story’s completeness, jurors compare a case story’s elements to the elements common to most every story. For instance, does the case story have a beginning, a middle, and an end? Are there causal chains that link various actions and events? If the story contains these elements (and others), the juror sees the case story as more coherent than alternative stories with less completeness. For one case story to be more coherent than an alternative story, it must also have consistency. For Pennington and Hastie, consistency refers to the extent to which the story lacks internal contradictions. A story with fewer inconsistencies would be judged as more coherent than one with more. Finally, to be coherent, the case story must be seen as more plausible than the alternatives. It must align more with how the jurors believe the world actually works.

Pennington’s and Hastie’s concept of coherence (comprised of completeness, consistency, and plausibility) provides a useful foundation for judging a client’s potential case story before trial.For some reason, their Story Model really resonated with me.

Pennington’s and Hastie’s concept of coherence (comprised of completeness, consistency, and plausibility) provides a useful foundation for judging a client’s potential case story before trial.For some reason, their Story Model really resonated with me.

Armed with my degree and knowledge of, among other things, the Story Model, I began my first full-time job as a trial consultant. (I worked freelance before and throughout my years in graduate school). However, when I first started consulting with clients on potential case stories, I found that the Story Model, while a good foundation, was not nearly enough to fully understand the nuances of what makes a good case story.

I recall attorney/clients who thought the case story they were going to tell the jury was a good story, even though, instinctively, I knew many were not.

Bad stories come in two basic varieties—non-stories and fundamentally flawed stories. Non-stories include presenting the case chronology as the case story. Chronologies sort of look like stories, events in chronological order, but stories are more than chronologies of events. (See our other articles to learn more about how chronologies are useful in constructing case stories but are not stories in themselves).

Chronologies sort of look like stories, events in chronological order, but stories are more than chronologies of events. (See our other articles to learn more about how chronologies are useful in constructing case stories but are not stories in themselves).

Just attacking the other side’s credibility is a non-story. The same is true for attacking the personal character of the opponents or their attorneys, or their morals, or their motivations, etc. In fact, very often these attacks have the perverse effect of reinforcing and even validating the other side’s case, especially when the other side is the Plaintiff. Consider the example of a trial in which a company attacks a supposed whistleblower who is suing for retaliation, trying to portray him as a terrible employee and person. The company’s attack itself makes the retaliation claim more credible, because based on their in-court behavior, the company looks like the sort of organization that would retaliate.

Ultimately, jurors tend to focus on those case elements that the attorneys themselves spend the most time on. The more time that is spent attacking the other side’s case, the more important and worthy of consideration the jurors perceive the other side’s case to be. One maxim we have for Defense attorneys at Decision Analysis is “Stop defending the Plaintiff’s case!” In other words, tell your own story, a counter-narrative.

There are other non-stories. “Legally, we did nothing wrong” is a personal favorite.

Then, there are fundamentally flawed stories. To paraphrase Tolstoy from Anna Karenina, “All good case stories are alike, each bad case story is bad in its own way.” There are too many ways a bad case story can be fundamentally flawed to enumerate here. Still, if I had to point to one factor that they all have in common, it’s that they don’t take the audience (the jury) into consideration enough. This is as true for bad case stories as it is for bad motion pictures.

Then, there are fundamentally flawed stories. To paraphrase Tolstoy from Anna Karenina, “All good case stories are alike, each bad case story is bad in its own way.” There are too many ways a bad case story can be fundamentally flawed to enumerate here. Still, if I had to point to one factor that they all have in common, it’s that they don’t take the audience (the jury) into consideration enough. This is as true for bad case stories as it is for bad motion pictures.

If the conflict of the case story is not compelling, the jury gets bored. If the characters are unrelatable, the jury just doesn’t care. If the characters and action in the story are unrealistic, the jury will not go along for the ride. If you tell them what to think or feel, like “the other side is lying, so you have to believe me,” the jurors assert their autonomy and resist your message. Like most people, jurors don’t like being told what to think or how to feel about things.

It was easy for me to spot the bad stories, perhaps because I was so familiar with them from my time in Hollywood. (I worked on some great projects and my share of schlock, too). But, while I could tell which stories were unlikely to persuade a jury, I struggled to figure out the best changes to suggest in order to rewrite them and make them better.It would take more time and experience.

my share of schlock, too). But, while I could tell which stories were unlikely to persuade a jury, I struggled to figure out the best changes to suggest in order to rewrite them and make them better.It would take more time and experience.

I continued to work and learn from more veteran consultants, but it wasn’t until about a half dozen years ago when I had worked on enough cases that things crystallized for me. I was finally able to articulate what elements made for a good case story and what changes could improve a bad one. To the extent that I had an epiphany, it was that the radical change in careers from Hollywood to trial consulting was really not such a big change after all. In both arenas, I’ve been helping people tell stories my entire career.

So (finally!), what does make for a good case story? The answer is the same things that make all good stories good. A good story has a well-developed main character with which the audience identifies on some level. At the beginning of the story, this character and others live in a status quo world. Everything’s alright. But then something happens which makes the main character want something, an itch they can’t scratch. When they try to get what they want, they run into conflicts and challenges. As they face and overcome these conflicts and challenges the main character experiences change and growth. In the end, they get what they want (or some other unforeseen version of it) and create a new status quo world. To put it simply, a good story reflects the human experience.

Now, that is the answer to the question on a grand-scale, but there are plenty of practical considerations as well. Here are just a few.

A good case story…

· Respects the jury. As discussed above, the focus of attention needs to be on the jury, not the advocate. Although the advocate’s client appreciates it (and even demands it), the advocate’s conviction is rarely as persuasive as the advocate or their client think it will be.

· Trusts the jury. Don’t tell them, show them. A good story reveals the opposing side’s failings through their choices and actions. They’ll figure it out.

· Teaches the jury. The world the plaintiff or defendant lives in is often unfamiliar to the jury. Consider jurors’ expectations and assumptions about that world. Create tutorials to provide the information the jury needs to understand you case story.

· Aligns with the jury’s values. Customize the story so that it reflects the values that the jury brings with them to the trial.

· Gives the jury a job. Give the jury a problem to solve. Juries don’t mind working; they just don’t want to know they’re doing it. Help define the jurors’ role for them.

· Simplifies. Einstein said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.” Everything in your case should be in service of the story you are trying to tell. Streamline your story, but don’t dumb it down to the point where it’s condescending.

· Is authentic. An advocate should resist telling a case story that they, themselves, cannot frame to be an expression of your own core values. The same goes for witnesses. Don’t tell witnesses what story to tell. Let them tell their own story, as clearly as possible. Authenticity and clarity are the hallmarks of effect witness testimony.

· Owns what cannot be changed. Every case has bad facts. I like the term “gravity problems,” things you can’t do anything about. A good case story is about human beings, with all their foibles and faults. Reframe the bad facts as best you can, but never deny or ignore them, that undermines your credibility.

· Is told with the appropriate tone. Discordance between a story and the tone with which it is delivered communicates insincerity. Be sure to align the case story being presented with the tone used to tell it.

· Is rooted in common sense.Notice that it is not “rooted in truth.” Commonsense may be true or untrue. For instance, that familial ties are stronger than convivial ties (“blood is thicker than water”) is commonsense, though not always true. The key is to be able to identify the commonsense principles in the case story.

Over the years my understanding of what drives juror and jury decision-making has certainly deepened. But the assumption I share with Pennington and Hastie in their development of the Story Model has not changed: jurors make up stories to try to reconcile the two sides presented at trial. The jury’s story is their story of “what really happened.” The jury will create a story about your case. You might as well take on the role of trying to shape that story by providing them with the best case story for your side.

John G. McCabe, Ph.D., is a cognitive psychologist and senior trial consultant. For over fourteen years, John has designed and performed a wide variety of studies (focus groups, mock trials, etc.) related to jury decision-making. Results from these studies have informed trial strategy in a wide variety of civil and criminal cases. He also assists in preparing witnesses, composing voir dire questions, jury selection, writing draft opening statements and closing arguments, developing trial graphics, as well as performing in-court observation and post-trial interviews with actual jurors. He earned his Ph.D. from Claremont, where his research focused exclusively on juror and jury decision-making and bias. In a prior life, John enjoyed a 15-year career in the motion picture industry, where he honed his understanding of storytelling.

John’s writings have been published in prestigious psychology and law journals and he has spoken at numerous national psychology and law conferences, law schools, colleges, bar association meetings, and Inns of Court. He has also published articles in For The Defense, Verdict Magazine, Trial Practice Journal, Women Lawyers Journal, Of Counsel, The Daily Journal, and TortSource, and his commentary has been published in the Los Angeles Times, Law360, and Bloomberg News. John has also appeared on television including CNN, HLN, and TruTV, where he discussed jury and juror behavior.

Recent Comments