“If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” — Albert Einstein

Sometimes you run across a real gem of an idea. Such was the case when I recently read the new (4th) edition of Cliff Atkinson’s Beyond Bullet Points. Atkinson consults with corporate communication executives, trial lawyers, and anyone else trying to persuade an audience through visual storytelling using Microsoft’s PowerPoint.

We all know that stories are a powerful tool to persuade an audience, whether you are a trial lawyer, a politician, a salesperson, or a manager trying to convince executives to pursue a new strategy. Data and evidence are great, but people can have problems understanding what data and evidence truly mean. Data and evidence packaged as a story is simply easier for people to take in and ultimately is more likely to change minds. As human beings, we are hardwired to think in terms of stories, and generally the simpler the story the better. However, and here’s the problem we hear about all the time from clients, what if the evidence in your trial is far too complex to distill down into a simple story?

Let me back up a minute and share a little about stories that will be helpful before we go on. Generally speaking, stories have three acts. In the First Act – The Set Up, we are introduced to the main character and the setting and see the status quo. Luke Skywalker lives and works on his uncle and aunt’s farm. Something happens and we then become aware of a disharmony or conflict involving the main character. Luke’s uncle and aunt are killed, and he decides to go with Ben to fight for the rebellion against the Galactic Empire and save the Princess. In the Second Act – The Action, the main character tries to resolve the disharmony, leading to an ever-escalating series of actions and consequences. Luke finds the Princess, Ben dies, and Luke escapes the Death Star. In the Third Act – The Resolution, the conflict comes to a head in a climactic confrontation. Luke destroys the Death Star. The action then subsides, a new status quo is established, and the story concludes. Luke and his mates are honored for having destroyed the Death Star and saving the rebellion. From inauspicious beginnings, he emerges a hero.

Each one of these Acts is comprised of a series of Sequences, which are in turn made up of collections of scenes. (For those in the storytelling know, I am combining sequences and scenes, for simplicity sake and labeling both as “sequences.”) A Sequence is a distinct collection of events called Story Beats. A Story Beat is the smallest element of a story. For instance, in the Death Star trash compactor sequence in the Second Act of Star Wars, “Escaping Storm Trooper fire, Luke and the others jump into a Death Star trash compactor” is a Beat. “A mysterious snake-like creature pulls Luke down under the surface of the water” is another. “The walls begin to close in” is yet another, and so on.

How can we map this onto a legal case? For instance, think of a witness testifying, covering four topic areas. Each one of these topic areas is a Story Beat. Perhaps the witness’ testimony communicates a Sequence in the story or perhaps other witness’ testimony will be needed to flesh out the entire Sequence. All of the witnesses’ testimony together should sketch out the 3 Acts of the case’s story. Not every case will map perfectly onto a 3 Act story. Some case stories rely on the trier of fact to fill in some of the gaps. Still, conceiving of and presenting a case as a story always has the benefit of engaging the trier of fact, increasing comprehension, memory, and the likelihood the trier of fact will use the information in decision-making.

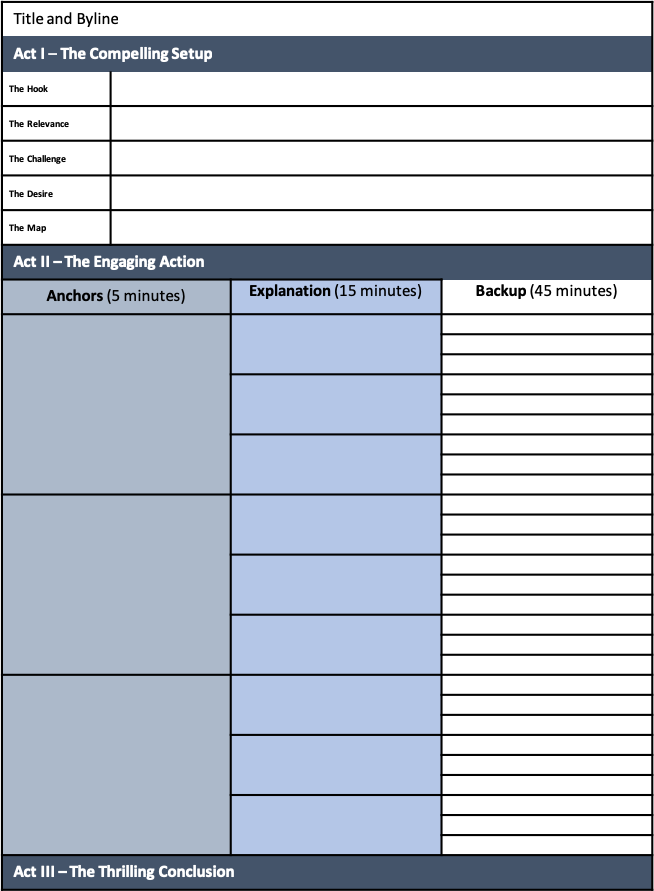

Now back to Atkinson. Atkinson provides a template to structure presentations (see below). The first section, Act 1, has information about why the audience should care about the presentation. The second section, Act 2, has three columns. The first column is divided into three equal parts, what he refers to as the “Anchors,” which are essentially three topic sentences. The middle column is divided into nine equal sections and is labeled “Explanation.” Note that for each Anchor, there are three “Explanations.” The third column is divided into twenty-seven equal sections and is labeled “Backup.” Again, for every Explanation, there are three pieces of Backup. The last section, Act 3, has space to describe the resolution.

As a consultant, Atkinson works with his clients to fill in the template: three Anchors, nine Explanations, and twenty-seven pieces of Backup. The process may take a day or two working alongside his client to decide what really are the three anchors of the presentation, what really are the three Explanations that go with each Anchor, and what are the three pieces of Backup that support each Explanation.

We simplified and tweaked Atkinson’s template and created what we refer to as the Twenty-Seven Points (see below) which focuses on Act 2 of Atkinson’s template. Information about Act 1 – The Set Up and Act 3 – The Resolution are subsumed into the body of our simplified template. In other words, a good case story always suggests why the audience should care about the case, defines the main character, the setting, and the status quo prior to the acts alleged as well as the resolution or desired resolution (i.e., a favorable outcome).

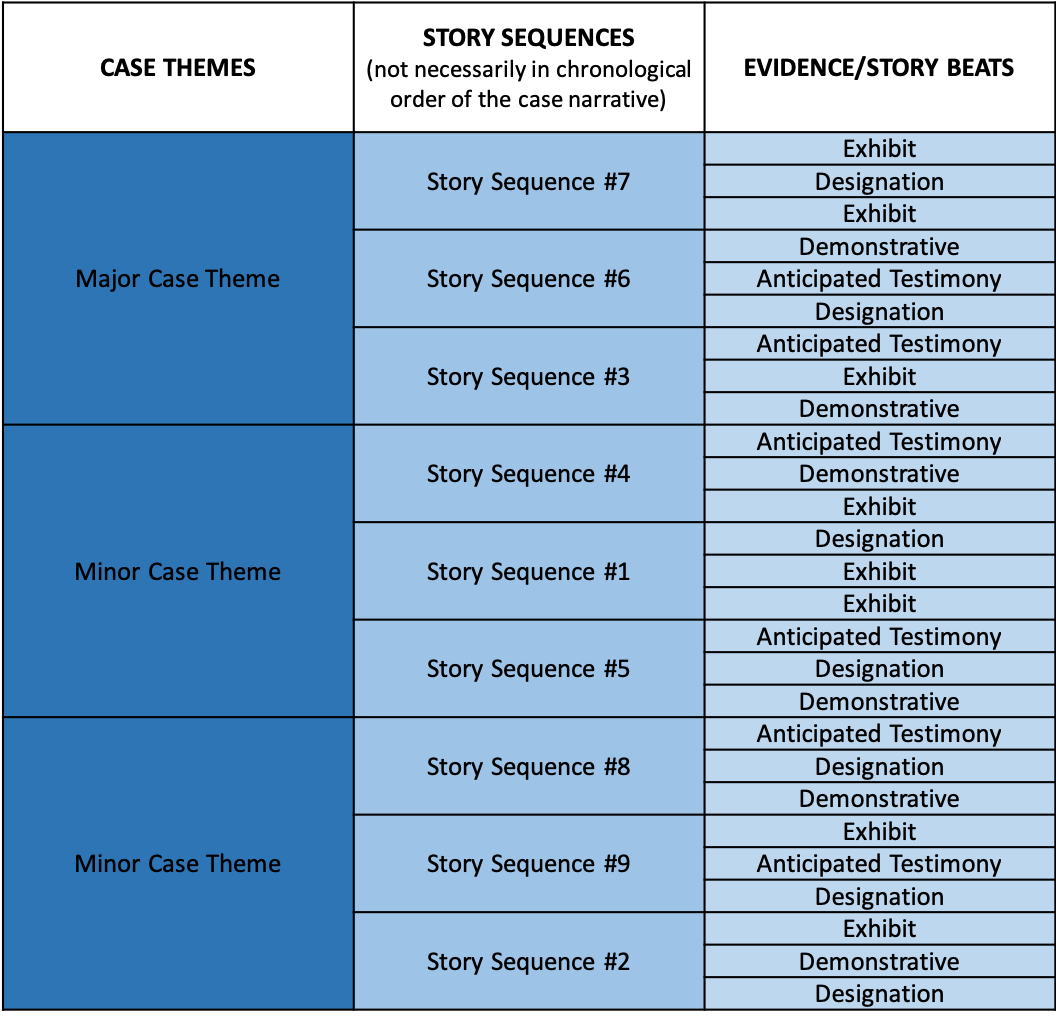

Instead of three Anchors in what was Atkinson’s Act 2 portion of the template, we develop (ideally through jury research, though not always) and insert three Case Themes, generally one Major Case Theme and two Minor Case Themes. A Case Theme provides meaning to the case evidence and law, while subtly directing the trier of fact to our desired outcome. Instead of Explanations, we enter nine Story Sequences, three for each Theme. These will not necessarily appear in the template as they would in the chronological order of the case narrative. Lastly, we enter three pieces of Evidence/Story Beats that support each Story Sequence. Totaling twenty-seven, these can be exhibits, demonstratives, deposition designations, anticipated testimony, etc.

A generic Twenty-Seven Points template.

We now regularly use this Twenty-Seven Points template with our clients for many reasons. First, the exercise challenges trial teams to simplify and streamline their entire case story so that it can be told using only twenty-seven pieces of evidence (exhibits, testimony, etc.).

Second, Twenty-Seven Points requires commitment to a story, if only temporarily. As trial consultants, we are storytellers. Using the evidence and law, we try to create the most persuasive story that those facts and evidence will allow. Still, like all communication, client – consultant communication is never perfect. The Twenty-Seven Points exercise ensures that everyone is in agreement about what the story of our case is. At the same time, everyone understands that the story will inevitably change as strategies evolve and new information is generated.

Third, the exercise of trying to distill down often complex cases requires all involved to make decisions. What is our story? What are the Themes of that story? What happens in our story? What evidence and testimony do we have to support our story? What background information will the trier of fact need to understand our story? And, often importantly, what evidence or testimony are we missing?

Finally, Twenty-Seven Points prioritizes evidence and testimony. We often hear from clients that they have a great piece of evidence. Does it fit into the story we want to tell? If so, great, we’ll use it. If not, a decision has to be made. If it is that great, the story may have to change to accommodate that piece of evidence. Alternatively, if it is extraneous to our story, it may not be included at all.

The overall methodology for designing PowerPoint presentations described in Atkinson’s Beyond Bullet Points is not without controversy. We are agnostic as to the overall recommendations of his book. However, we do believe this one aspect of using a template to help distill a case down to its essence is incredibly useful.

John G. McCabe, Ph.D., is a cognitive psychologist and senior trial consultant. For over fourteen years, John has designed and performed a wide variety of studies (focus groups, mock trials, etc.) related to jury decision-making. Results from these studies have informed trial strategy in a wide variety of civil and criminal cases. He also assists in preparing witnesses, composing voir dire questions, jury selection, writing draft opening statements and closing arguments, developing trial graphics, as well as performing in-court observation and post-trial interviews with actual jurors. He earned his Ph.D. from Claremont, where his research focused exclusively on juror and jury decision-making and bias. In a prior life, John enjoyed a 15-year career in the motion picture industry, where he honed his understanding of storytelling.

John’s writings have been published in prestigious psychology and law journals and he has spoken at numerous national psychology and law conferences, law schools, colleges, bar association meetings, and Inns of Court. He has also published articles in For The Defense, Verdict Magazine, Trial Practice Journal, Women Lawyers Journal, Of Counsel, The Daily Journal, and TortSource, and his commentary has been published in the Los Angeles Times, Law360, and Bloomberg News. John has also appeared on television including CNN, HLN, and TruTV, where he discussed jury and juror behavior.

Recent Comments